Memories of Mr. Harry Tennyson Durham of Skelton, East Yorkshire

These fascinating memories of his youth were written by Harry Durham in his later years and kindly passed on to me by his granddaughter. He led an interesting life, growing up in the cottages adjacent the NER Goole railway bridge at Skelton near Howden. After leaving school he was apprenticed as a joiner to Goole builders Platt and Featherstone. He also worked at Goole shipyard.

His mother Lydia Wainman was born at Laxton, one of the four children of Emanuel Wiles Wainman and his wife, the former Grace Bowes. Emanuel and Grace married in 1880. They eventually retired to Rose Cottage, Laxton and celebrated their Golden Wedding in 1930 in Skelton schoolroom.

Early memories

"I was born on July 14th 1911 in the fourth house in First Row in the village of Skelton near Howden, East Yorkshire.

My father Trevor Durham was part of a "railway renewal gang" working in Hull, after which he was transferred to Goole Swing Bridge as a steersman in the top bridge cabin.

My mother was the cook at Mr Craggs of Brough, near Hull, the owner of the Goole Shipbuilding yard. Before she married she was Miss Lydia Wainman.

Harry's parents: Lydia and Trevor Durham

After my parents moved to Wards' Cottages in Skelton, my brother Eric was born; then, four years later, Trevor, my younger brother.

I remember around the age of seven years old, I attended Skelton school. The teachers were Miss Milne for the senior class and Mrs Brixome for the infants. Mrs Scholfield, the squire’s wife [from Sandhall], used to call twice a week at the school on horseback. I remember that when she entered the school we all had to stand up and say "Good morning Ma'am". Also we had to touch our hats and respect the squire on every approach!

The village road was very busy in those days. Anderton Tillage Works at Howdendyke brought all the bagged tillage to Skelton railway siding on big steam lorries with huge block rubber tyres. The rear wheels were driven with huge chains geared to the steam engine. Skelton siding was also very busy at potato time every year. A horse and rulley, with up to five ton of bagged potatoes, was pulled by two very smart horses. One man at the siding, Walt Thornton, was the weigh man who checked all the weights before they unloaded into the empty railway trucks on the loading dock.

How Grandfather got his car

The only motor car in the village was my Grandfather's, Manny [Emanuel] Wainman's; he was a real comic. How he got it was this – he was boiler man on the swing bridge, working shifts of eight hours: 6am to 2pm, 2pm to 10pm and 10pm to 6am weekly. In his spare time he did gardening and was quite good at beekeeping. He had been working quite a long time at Dr. Brown's at Howden [and one day] Dr. Brown [who lived at Laughton House in Hailgate] came into his yard while Grandad was busy with the Doctor's bees and talking to the Doctor's wife, both of whom thought the world of him. Grandad had fixed them up with new hives and also bees and they were both delighted. Dr. Brown turned to Grandad: "Now look here, Wainman - you have been very good and worked hard in our garden for the last year without payment of any kind. Now please, please let us give you something for your labours; can you suggest anything, Wainman?" My Grandad said, "Yes, Dr. Brown, there is something I would like very much, but I've no money. I would like your old motor car." "For your bloody cheek," Dr. Brown said, "You shall have it." That's how Grandad got his car! I remember the two big brass head lamps; the shed is still there which he kept it in.

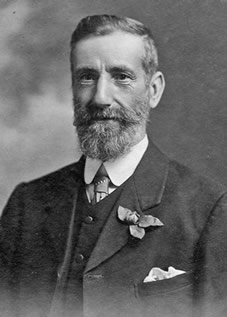

Harry's grandfather: Emanuel Wiles Wainman

Life at Bridge Cottages

During this time we had moved to No. 5 Goole Bridge Cottages. My Grandfather lived at No. 2 in the same row. This was a good move for Dad as he was near his work. The man who left No. 5 had retired; his name was Mr Haigh and he also had worked on the swing bridge.

This house was two upstairs rooms and one downstairs, with a built on kitchen at the back. Eric and I slept in a double bed in the back room, Trevor in a single bed, and Mum and Dad in a double bed in the front room.

Of course, in those days it was chapel every Sunday; a good mile walk. Grandad and Mr Tipping were the preachers and Mrs Brown played the organ. These two men are always outstanding in my young days, even today when I look back. They had never been to school and could not write their own names, but their dedication to prayer and the Gospel was one of the things I shall never forget. [I remember] their hymn, "The Gospel Bells are Ringing" - they gave that hymn some stick!

Saturday was our treat day; Arnold Bailey from Howden came with a horse and cart with sweets, bread, fruit etc. We got one penny each – two long Spanish [liquorice] boot laces 1/2d and a bag of coconut crisps 1/2d. For this, we had to collect driftwood from the river banks; all of this was stacked down the hen run to dry for winter fire fuel. Mum would do all the cooking with a firegrate oven – no electric or gas. We had to keep her supplied with what she called oven sticks. Her light cakes warm on the hearth, filled with black treacle, were out of this world - did we scoff them!

Butcher Lilley called twice a week: Tuesday and Saturday. Mum was a member of the Co-operative at Howden; her number was 13830. Fred came for Mum's order and it came on Friday; on Tuesdays our paraffin came for the lamps. We had a modern Aladdin lamp hung in the centre of the room. Dad fixed a switch light on the stairs from two batteries to a small bulb.

We all bathed in Mum's wash tub on Fridays, when she lit the copper fuelled with stick and coal in the wash house outside. Our water was from rain tubs - high wooden casks, 5ft high x 3ft diameter. In very hot summers with no rain, [the] railway would send us a tender full of fresh water and fill all our tubs. We emptied our soil toilets ourselves; sometimes in the river, other times wheeling it on the barrow to the garden.

Dad got our coal - all the five neighbours would get together. Dad ordered a 10 ton wagon from Thorne colliery [and] borrowed a horse and cart from a farmer, then all would help to load and unload to each coal house, each load weighed on the siding's scales.

School at Hook

When I was around 10 years old Dad didn't think I was doing so well at Skelton School, so he arranged for me to go to his old school at Hook. This meant me crossing the river bridge daily, which is nearly a mile long - also very dangerous - but off I went. In very bad weather I stayed with Grandma Durham (Grandad Durham had been dead a few years). Grandma said he was groom for Kelseys'; big horse breeders. A horse called 'Sceptre', on a picture on our wall at home, was born at Kelseys' under Grandad's care; it won four of the Classic Races in one year. [William H Durham, aged 23, born at Water Fulford, was a groom for Thomas Kelsey of Ousefleet in 1871.]

At Hook school was a master, Mr Charles Tong - clever chap, very strict. He used to stand all of us single file round the room, each with a copy of Charles Dickens; "A Tale of Two Cities" was the book. I remember that each one he called had to continue on the exact word where the [previous] reader left off ... the times he caught me out and out came the 3 foot cane, like a whip lash on the finger tips and up underneath!

One outstanding memory at Hook school was of Harry Morton - poor kid. He was at the far end that day. Harry's dad was the Hook coal merchant and, having 1 1/2 hours for dinner, [Harry] had to run bags of coal on a sack barrow to orders in the village. The lad's hands were always black-bright and, like me, he was not a brilliant scholar. He came in for a lot of trouble. [That day], for some reason, he gave a big shout - "HOO!" - someone had stuck him with a pin. "Come to my desk, Morton." Old Chas got his stick, and wallop! Whether he had caught a sore, chapped with the coal bags, I don’t know - but Harry went mad. "You BUGGER!" he said, and kicked Chas on the shin bone. Chas got hold of Harry by the neck and, laying him over his desk, belted his backside with the cane. Harry ran out of school cursing.

I got a good hiding when he asked me to name him a fur-bearing animal. I said, "Parrot, Sir."

Pig killing

At weekends I would go with Grandad pig killing; this was great fun. He used to charge 5/- per pig kill and cut up. People used to collect his scalding tub on a wheel barrow the day before the kill. The pig was not fed for 24 hours before, so the bowels were empty. One day we went to Saltmarshe to kill a 10 stone pig. Grandad collected his tools, tied the mallet to the bar of his bike, tools on the handlebars, jumped on his bike and I stood on the step he made for me on the back wheel, holding on to his shoulders. Off we went to Saltmarshe - 3 miles.

On arrival it was a 10 stone Black & White Saddleback, belonging to an aged pensioner. The process was [as follows]: Grandad had to band this pig with a loop of rope round its nose, then lead it to the gate post, tie the rope to the gate post and then the pig would pull to get loose. Grandad would straddle the pig with his knife in his mouth, ready to cut its throat, while holding the punch on the pig's head. When he nodded his head I hit the punch with the mallet - down the pig went, stunned. Grandad then cut the throat and working the front leg to get the blood away. Making sure the pig was dead, he removed the punch and re-entered his long steel knife in the brain box to make sure the pig was dead. He also trod on the toes to make sure the animal was dead.

Then he put the big scalding tub on its edge alongside of the pig. Grandad got hold of the pig's front leg it was laid on and me the same at the back leg. Then, together, we pulled the animal into the tub, dropping the tub flat at the same time. Now, with boiling water, he would start to scald it, pouring water over the pig until all the hairs were scraped off. The head was cut off and the toe nails pulled off. The back legs were cut parallel with the leg for the sinews on which the "comerill" is entered to the notches each end. The three [tripod] legs were placed over the tub with rope and pulley at the top. Then the rope end was tied to the centre of the "comerill" and up in the air [went] the whole carcass. The belly was cut open first; [we would] collect the gall and throw away. After removing the intestines and the backbone, the chine was chopped each side from the bottom to neck. It was left 24 hours to set, after which it was cut up to shape - hams, shoulders and sides, back chines chopped up and all salted down for 3 weeks in dry salt. Today this is done in salt brine.

Sport

Now, sport in the village was quite good. Skelton [had a] cricket team and village institute, with a full size billiard table which was 2d per 20 minutes. This money paid for lighting and coal together with card games. Football was Howdendyke Rovers. We used to walk to the game on Saturday afternoon, approximately 2 miles. [There was] no charge for entry or round with the cap at half time, but both football and cricket were sponsored in the winter months with dances at the school room; also whist drives.

PC Jacks

I loved a catapult – [once] while out round Grandad's field on side of the road, a pigeon flew out. I let bang at the bird in flight, not seeing PC Jacks turning the corner on his bike. I knocked his helmet clean off! He went straight to our house and reported to Dad. That was another good belting I got.

A week later I found a body of a man in the river – of course, one had to report this to the police. PC Jacks came once more and we dragged the body out of the mud. One was supposed to receive 7/6 for finding a body; Dad might have got it - I don’t know. But I remember him telling me finding a dead body was 7/6 at the East Riding side, 5/- at the West Riding side of the river.

This man was a Mr Baxter, a sailor off the SS Saltmarshe of Goole.

Bush beating at Sandhall

Another highlight to look forward to was bush beating for Squire Scholfield each year from around 1919. This was great sport on around 100 acres of potato land, very flat and open. The great drive was by men and boys across these huge fields to drive all the hares towards the guns [who were] waiting in the middle of this open land behind small thorn hedges built for the job. The guns consisted of squires, colonels; all sporting friends. This drive occupied all the morning. We had to beat the ground with sticks, as hares only burrow about 3 inches underground. They could move in full flight. Some of the older hares knew the game and would take to swimming the river, which was very wide, rather than face the guns. Once a hare was in full flight and a man was on his bent knees waiting to stop him running back, but the hare hit the man in the chest and bowled him over with high speed.

We collected 80 to 100 hares that morning, besides pheasants and partridges. After collecting all the game and loading on to the cart, we all went to the hall for dinner.

What a spread, great big dumps, meat and veggies; was we ready for this big meal. What a good cook Phyllis Bayston was. After a mug of tea for the lads and beer for the men, we were ready for the afternoon.

The afternoon was beating the thick woods for pheasants etc, as we stumbled our way through the undergrowth thicket shouting "back over to the right, Sir" or "to the left" as the birds took flight. [There were also] rabbits, moorhens, partridges. This went on under the gamekeepers' guidance until 5 o'clock, then we loaded all the game and [went] back to the Hall.

Mr Scholfield would thank everyone individually, asking you to take home which you would like. Mine was always "A hare, Sir, please". I was proud to take this big hare home every year. Mam used to 'jug' it: stuff [it] with black cloves, put [it] into our enamel washing bowl, 18" across, 5" deep, and into the coal oven. With dumplings and thick gravy it was sat in the middle of our square kitchen table and five of us soon cleared that lot.

Now, while I was at the shoot, I used to pick all the used cartridge cases up in good condition - these were for Grandad; he had me trained. My pockets were always bulging out when I got home.

My Grandmas in Hook and Skelton

After weekends, Monday morning and back to Hook school. I had to cross the bridge each day. Dad trained me to use great care, what to do and where to go in time of being caught on the bridge the same time as a train. Before setting off I had to observe a signal at Hook Road Bridge. With a clear light, I could proceed; if no light, stand until the train passed.

With Dad being in the top cabin, he was on duty morning shift one week, afternoon shift the next. When on night duty the other two men, Mr Bill Ramsey and Harry Wallace, were very good to me.

In thick foggy weather, it was arranged I stayed with Grandma Durham [Mary Ann Durham, nee Campbell] at Hook. She was a real "Old Dear". Grandad [William Henry Durham] died 2 years before I went to school. Grandma Durham lived in a little bungalow covered with ivy - just two rooms, bedroom and kitchen. The kitchen had a tiny coal stove with little oven, 9” x 9”; very small - but how she could make Yorkshire Puds. My dinner was always waiting at noon and nice Tit Bits for tea when I stopped. I always had to kneel down and say prayers with her before we got into bed. I always slept with both my Grans in a double bed. Gran Durham was very religious - only two newspapers allowed in the house: "Sunday Companion" and "Christian Herald". All this would be around 1920.

When I was at home and Grandad Wainman was on night duty, I stayed with Gran [Grace Wainman, nee Bowes] the whole week. Her double bed was draped with a long hanging curtain from the tall brass bedhead tubing and she had a feather bed.

Poor dear, she suffered from shock through my Uncle Arthur being killed in 1916 in the Great War. I caught her many a time with a tear in her eyes, looking at the photo in the locket she always wore around her neck on a gold chain. I wonder what happened to that.

Harry's gran: Grace Wainman, nee Bowes

She was a very hardworking woman and used to work in farm service as a girl. Start washing 4 o'clock in the morning, until 7 or 8 o'clock at night. I might have been spoiled with being the first grandchild, but I could not do enough for them both.

The words of Vicar Chamberlain at the graveside of Gran Durham were, "If there is a heaven in the next world, this lady is sure to be in it".

The swing bridge

Now, the swing bridge I crossed daily; I used to visit Dad and spend hours in the top cabin with him on the 2-10 shift. His duty was to swing the bridge for river traffic; it was very busy in them days. Tugs pulled six, sometimes eight, barges and with a strong tide running it was very important to the tug captain and so Dad, if he could give the tug a run, would stop a train.

The point was, if he had accepted a train, the tug would have to round up all the barges and hold them against a strong tide, having to proceed through the bridge, barges first. This took time for both and rail traffic was very heavy too.

When Dad wanted to open the bridge for river traffic, he had to strike the up line bell five times and down bell five times. On getting a reply, he pushed the centre lever, which cut all contact with rail traffic. [Then he] pushed No. 1 lever to lift the hydraulic jacks in the bridge ends, thus leaving bridge ends free to turn, 'jamming'[?] on the bolt in the centre that draws out a pin in each bridge end and turning the centre handle that sets the hydraulic system into action. The big spans turn at great speed.

A megaphone was used to shout through to tell the ship [that] the bridge was open in foggy weather. A powerful spy-glass was in the cabin to read the name of the ship, because every ship's name and time it passed through the bridge had to be booked.

Grandad's job was boiler man on the jetty; his duty was to keep steam in the boiler. There were two boilers, one used the first week then rested, and the other one used alternately and washed out each time.

Steam in the boiler is raised to drive the steam engine in the engine room which pumps up the hydraulic ram that is 3ft diameter and I should estimate 150ft long. It goes 80ft below the bed of [the] river. This power drives [the] bridge round on big wheels, 2 ft dia, 2ft wide, each on a shaft to the centre pin; a wonderful construction.

Goole Bridge on the NER. Locally it is known as either Skelton Bridge or Hook Bridge, depending on where you live.

How the swing bridge works

Dad rings below to say he wants to swing. After the bridge is parallel with the river, the accumulator, or ram, is dropped. Grandad then sets his steam engine going that pumps water pressure back into the cylinder that brings the accumulator to the top again. A long chain from the centre top of the accumulator in the house, with a large weight on it, is continued to the engine house to another weight that drops in a bucket and makes a noise. Grandad in the engine room stops the engine when the weight hits inside the bucket because the ram has taken the weight in the accumulator room. Now the bridge is ready once more.

No trains on Sundays

At this time trains could not run on Sunday; it was agreed in the sale of the land to the railway from Colonel Saltmarshe. That condition held for years. The bridge was open to river traffic only from 12 midnight Saturday to Sunday midnight. That was [why they had] a bridge boat to travel to and from the centre jetty. Dad and Mr Alf Tomlinson had some rough winter rides - I've watched them. I was pleased to see the boat arrive each way.

The tugs that used the river in those days, I remember, were City of York, Robin, Lancelot, Arrow and Ouse. Sloops with huge sails and a wide lee board came in numbers just through the bridge.

On the Howdendyke side, sanders used to work the tides three men to a barge; two men at the winding gear and one man with a long pole with a huge leather bag on the end. This was thrown over the side; the man with the pole stuck it in the sand at the bed of the river and then the two men began to wind up the bag full of sand. This was lowered and tipped in the barge. The hold was used for best washed building sand, no salt in it. These men would fill a barge, 100 tons, in a day and sail back to Hull.

I was never bored when I was with Dad or Grandad. On a wet day it was nice and warm in the boiler house. Grandad had a private locker on the jetty. I took the spent cartridges from the shoot to him; he would set me on knocking out the copper caps on the brass ends. Then he would fix in a new one. After this he put in gunpowder and shot and, with a little machine like a pair of tongs he used with his hands, he clipped a new cardboard cap at the other end. He had Eley cartridges for his double barrel gun. He was really a clever chap (I've since realised). He had a hand forge in the workshop on the jetty to do repairs to plough shares; any ironwork that broke, he could mend it.

My Grandma would say, "Manny, that oven won't draw" - he used to put a little charge of gun powder in the top of the oven [which] cleared it with little or no mess. People from all over came to him with clock repairs; he did all these on night duty. He was also an expert with bees or removing wasps' nests from old house gable ends.

George Hart at Pasture Farm let him have the one acre field in front of our row of houses. He borrowed his horse and plough, sowed it with peas, and made quite a sum. But he saved George Hart pounds in other ways; everyone in the row had pigs - he butchered the lot and many more.

Salmon fishing

One lovely afternoon I was taking my Grandad's tea, about 5 o'clock, while he was on duty. It was always my job, to save Grandma the trouble, and was an excuse to be with him for an hour. We were both sat on a long saw stool at the end of the jetty facing up river, Grandad eating his tea. All of a sudden, little fishing boats came from all angles chasing salmon; it was nearing high water and what a sight. Salmon were being pulled out by the dozen, big fish 18 to 25lbs. One boat, Arthur Adlit's [Abbey?] had 15 big fish in the bottom. Each boat had a 3ft dia net with 1" mesh fastened to a 6ft handle and they netted the fish, then lifted the fish into the boat. With the river water thick with mud, the salmon had to keep coming up to breathe. The fishermen chased to get to the fish first. The men pushed the boat with two oars and stood behind, pushing forward to give them a better sense of direction. Salmon were killed by a blow on the head with a bottle.

1925 trip to Wembley

In 1925 all the village was very happy. Mr Scholfield, our squire, arranged to take us, the children together with our parents, to the Wembley Exhibition, travel all paid. This outing was a great success and was the first time I'd ever seen London. We went on a conducted tour round the exhibition, most interesting, then were given lunch, after which we were taken on a bus tour round all the sights of London. Afterwards each of us was given an exhibition mug with 1925 on it.

The biggest joke of the day was when Jim Clayton got lost; he went up to a policeman and said, "Hi mate, have you seen sight of Skelton party, I'm lost?"

New occupants

Soon after our visit to London we had a sad loss in the row. Mr Wallace at No. 3 died; a shock to us all. Mrs Wallace had to move out of her house into Reedman's Row. His job was taken by a man called Mr Hinch who lived at Laxton. He didn't want the house - it was empty for a while. Then, one day, up came a furniture van with Mr and Mrs Jefferson [William and Amy Jefferson] and three children, two girls and a boy.

They had the window to take out at the front to get the furniture in. I had just been to feed our chickens and pig and was returning home from across the road with a tin full of eggs. I noticed, sat in the window, a lovely plump lass - what a smashing pair of legs hung down. I just could not resist asking her if she would like an egg for her tea. Bless her, smiling she said, "Yes". This is how [my wife Vida] and I met at 14 years old and she's been taking eggs out of my basket ever since!

Farm work at Sandhall

At 14 I was ready to leave school and get a job. My first job was at Sand Hall Farm, 12/- per week. My duties were carrying milk to Sand Hall from the farm at 7am in the morning; after this I had to put an old horse in the cart and go fetch a load of turnips to feed the cows, [then] tip them in the barn to be chopped up for next morning feed. After putting the old horse in the stable, I had to go down to the potato riddle at the end of a mile pile. This was a hand riddle - one man turning the handle, one man feeding the potatoes on with a potato [?] and one man taking the full bags off the end. The mesh on the riddle was around 2"; all the small potatoes ran through a trough at each side of the riddle with a basket under each. This was my job to keep the baskets emptied. [The] faster he put the potatoes in, the sooner my baskets were full.

We had a lot of thrashing days at the farm. Some days I was given chaff to carry in a large sheet to the fold yard; another hard day was cutting strings on the machine or standing feeding wheat into the drum. Some of the sheaves were very heavy for a 14 year old. I was very tired at night but continued the work there for quite a while.

Paying doctor's bills

My 12/- per week pay was handed over to mother at weekends. She had much to do to pay her way. Dad's wage was around 50/- per week, but he put some extra money in my National Deposit Bank. It was paid to Mr Holt of Pasture Road, Goole. Each of the family had a book; the amount of cash you had in the bank, one could draw three times the amount out in sickness. Of course, Dad had all the family's doctor's bills to pay.

Doctor's charge was 7/6 per call and 1/- for a bottle of medicine. So the scheme worked if you had no sick bills; you had money and interest in the bank. One's contribution was 2/- each per month.

A new job in Goole with Platt and Featherstone

Now, I asked Dad if I could change from farm work as this was not for me. I was lucky. Dad met Mr Frank Platt and Mr Featherstone, the joiner of the firm, sent for me. He gave me a job as an apprentice, at 7/6 per week. I had got to ride a bike by now so Dad bought me a second hand one from Howden, at Bob Watson's. I was top of the tree; this was great.

The joiner's shop on Hook Road was an ex-picture house; it had ten benches in it, with one man and an apprentice at each bench. My first work was sweeping up shavings and chippings etc.

I settled in here, very happy, just three older apprentices – Frank Easton, 'Boyn' Watson [Herbert Boynton Watson?] and Bert Stebbing. My boss was a real gentleman, but very strict. Harold Watson was the machinist and foreman, another real 'Toff'; both these men were clever joiners.

Our shop's machines were a band saw, planer and saw, all powered with an electric motor; we also had a hand mortice machine. We made windows, doors, cupboards, staircases for 20 council houses. I was hand carting, painting etc for six months and then my chance came to go on the bench. First thing I made at dinner time, because I had to stay for dinner, was a plant stand for my Gran. She bought me a full set of chisels - these were my pride. She gave me lots of money for tools. I was still travelling over the bridge home; Dad got me a permit to cross the bridge.

Porters' Timber Yard

One of my duties as youngest apprentice was hand carting timber from Porters' Timber Yard in Bridge Street, a good mile away. It was hand-cart work and the way the Porters Timber Yard loaded my cart at times was far too excessive to push up the hill on the approach to West Dock Bridge in Bridge Street. But when I was struggling, some passer-by would give me a push to the top. I found Goole people were always willing to help – I was only 15. But by oiling the wheels and getting an even load, I soon mastered the job.

I made some good friends in the timber yard. The men, with leather pads on their shoulders, carried and stacked new timber. They could unload a barge from the dock side and walk up a plank to a height of 20ft to stack it with laths between to let the air in to dry, and also with the heart of each piece down to keep the weather out.

Arthur, the machinist in the mill, showed me how the massive machine worked - his wonderful machine was used for making every kind of mouldings. I couldn't get there enough, it was so interesting. A rough [piece of timber] pushed in at one end came out a length of cove moulding at the other. I learned a lot about different timbers from them chaps.

Westfield Road site

Another duty as the youngest apprentice was taking windows made in the shop to the building site in Westfield Road off Pasture Road.

I met some really nice chaps there. There were about six joiners on that site then and the same [number of] bricklayers. These chaps had such pride in their work, neat; everything had to be just so. I thought to myself, I’ll never be able to work to this standard. The brickwork was so neat with black mortar and red stock bricks, but again I saw where and how the windows fit, door casings and doors.

The black mortar was made on the building site for the bricklayers. [There was] a large wrought iron round bowl-shaped trough, 8 or 9 ft in dia, 14" deep, revolving round, driven by a farm tractor with a belt inside. In the trough were two heavy wheels, 2ft dia, 18" wide, turning from the centre, crushing clinkers and cinders from gas coke ovens at the gas works. Ground to powder with lime and a little cement added, this set very hard indeed.

Also a large pit was dug 30ft x 30ft x 3ft deep. This was filled on site with washed quick lime and used, after it set like jelly, with sand, to plaster walls. Horse hair was added to the first coat and it was skimmed to a lovely white on the last coat.

Whatever was being made in the joiners' shop, I had to transport to the joiners and bricklayers on site. I remember to this day one embarrassing time – Harold, my foreman, sent me with a flight of stairs, three windows and three newels. I loaded my cart and off I went.

They were waiting for these stairs to fix and on arrival I stayed to watch. Old Nick Gent was fixing them and found he was a step short. "Hi boy, go and tell that bugger at shop he has a step missing." On saying a step is missing to Harold on return, he just turned to me and said, "Put this window on the cart for George Davies, the bricklayer, then go and tell Nick to build a box step on the bottom as it was intended and go back to night school, that's all!"

I had, always, very high respect for Mr H Watson and Mr Featherstone. When they measured any work it was the correct size because, I found out later, it was measured with laths. Today I find everything's wrong from a draughtstman's table because they have no practical experience in the building trade.

Life after work

Home in the summer time on the river bank was always a pleasure. After work, as I got older and more confident, Dad would let me take the bridge boat out around high water. I could scull quite strongly this way, one oar in the stern. Dad and I travelled by boat to Uncle Jim's at Hook on a pleasant evening. I got my tame rabbits from him. He was a real character for fun; he liked a drink of beer too. After a jar or two he was good company. He could play a concertina great. We went to play quoits at The Sotheron Arms – there were two clay pits some twelve feet apart, six feet in diameter with a steel pin in each centre. The skill is to ring the pin with a 6" or 9" steel ring, three of these [for] each player. We had some good nights out in the pub yard.

At home down the hen run, we had rabbits, bantams and a goat (a nanny). We made a cart and yoked it in like a horse - travelled all over, of course leaving a trail of droppings. When at school in the day, Dad tied her to two railway heavy iron chairs, but she always broke loose. Dad caught her stood on her hind legs eating the buds off his young apple trees. That did it - we had to get rid. Dad sold her to Tommy Abbey at Howdendyke.

Flooded

One year on the spring tide, the highest of the year, the river overflowed its banks and we were marooned; our house was the only one without water in it. Dad struggled and got our 18 stone pig into our back kitchen. Our chickens were safe as the hen houses were stood on 2ft high stilts. It cleared us out of rats; our ducks were on the floor but they could cope.

Trixie the cat

Dad had a black she cat, Trixie; they thought the world of each other. She had dozens of kittens and Dad drowned all but one each time. One election time a man came round canvassing for votes with a big black retriever dog. Dad answered the door, cat with him, with its back up at the dog on the doorstep.

"If I was you, Durham, I'd take your cat away or this dog will worry it," said the man. "I've warned you he does not like cats."

Dad says, "I'll just have 2/6 on the cat."

As soon as the dog put its nose through our door, Trix was on his back with her claws deep in. The dog travelled 30 mile an hour down the road (Trix still there), yelping. The man whistled the dog to come back and said, "I would not have believed it." Dad told him, "She’s a special breed - the bigger the dog, better she likes them! She has a baby kitten in that box; would you like to see it?"

Dad told me he'd watched that cat fetch a whole nest of wild rabbits by walking at low tide at the water's edge until in line with the young rabbits' nest; [she would] grab one and walk back with it trailing in her mouth for the kitten. When the tide rose, it took the scent of the cat for the next day.

She lost a paw in a rat trap; it was pitiful to see her go to him, but he nursed her through. She had lost the bottom of her front paw already in Dad's chair. He had that breed of cat for 30 years. Trix lived to be an old age but she finished up with another leg in Blyths' reaper and gangrene set in. How he drowned her, I don't know.

The Jolly Sailor, Skelton

The Jolly Sailor Inn at Skelton, owned by Mr Hutton in the early days, had a jetty in front of it, old and battered, with a willow tree hanging over the stern of an old schooner by the name of May Flower. The forward bowsprit had a lovely painted figure of a lady. This boat was laid there years and in the end it was towed to Hull or Goole, but it belonged to a man called Hope Caisley. He lived in the end house of the row of cottages. This man had a long beard and always wore a captain’s cap. I was told his parents [William Caisley and Mary Hope] were the owners of the sailing ship repair yard that existed next to the Jolly Sailor Inn. I would love to know if the figure of a lady at the side of Plymouth Dockyard is the same one belonging to the May Flower.

The Jolly Sailor at Skelton

During the 1914 – 1918 war, ships of a huge size were built at Hook Shipyard. One in particular was launched one Monday morning. It shot straight across the river off the slipway at speed and stuck in the river bank at the Skelton side.

Two ferry boats were in service then too, one at Boothferry to carry horses and traps, trucks etc. The [other] one [was] at Howdendyke to carry to carry men with bikes etc, but both were kept busy.

Scarr's Shipyard at Howdendyke built barges to carry 100 tons.

News of the river

We always had river news every week of some kind at Skelton. Such as:

"E P Scholfield's loaded 400 tons of potatoes on a river barge at Sand Hall Wharf Dock."

"A school boy swimming at Goole river point at low water, swam across the river but failed to make the journey back and was drowned."

"A barge hit the centre pier of the bridge, a woman was knocked overboard and drowned."

"A grampus as big as a whale came up river chasing a glut of salmon but was found dying on mud flats at low water. Had to be towed out to sea because of the unhealthy smell in the warm weather."

"All river traffic was stopped because of thick ice blocking the river."

"Aeger ploughs through at the height of 3ft in spring tide flood."

The bridge on fire

Contractors had been working on the centre pier of the swing bridge for 12 months. On March 21st 1921 Dad had ordered me to bed after tea for breaking Mum’s bedroom door knob the night before. It was a lovely night but a strong breeze was blowing from the north. The tide was low, I was looking through the back bedroom window, and my eye caught a timber on fire between the top of the jetty and low water. On shouting to tell Dad, he scoffed, thought it was an excuse to go out. But sure enough, 10 minutes later it was an inferno; wind got hold, pitch pine timber soon ablaze. Fire engines from Howden were called, also Goolies, but they were useless to get to the centre of the river with pumps, pipes and hoses. Grandad was on duty, nearly lost his life fighting the fire in the engine room - what a night; the fire just raged. Next morning the huge water tanks on the jetty were hung down, supports burned from under them. Of course, Grandad hit the paper's headlines the next morning, interviewed the next day by all the big bosses from Hull in the glass carriage. He took them all in his stride, no difference to him who they were. Before they went back he had sold them some of his apples and bees' honey. But he had been near enough to suffocation in the engine room.

Life as an apprentice

As I said, our joiners' shop was an ex-picture house. My boss Mr Featherstone was very fair and honest. We had a sad loss in the shop. Suddenly we lost Bert Stebbings, our third apprentice in line. The little time I knew him, I found him a real nice lad. His father [also Herbert Stebbings] was a bricklayer with our firm on the building site.

Later, our boss brought the apprentices up to full strength. I was put on the bench work with a very good craftsman, Mr E Settle, for some three years. They were my happiest apprentice days.

On Bench 1, top end of the shop, was Sid Howard "Gee Whiz Sid" and Claude Easton with him at the same bench.

On Bench 2 was Sam Proctor and apprentice Frank Easton, the eldest of our 6 apprentices.

Morris Tebb and Walter Tice were on Bench 3.

Fred Lilford and Fred Rowley were on Bench 4; two really dedicated joiners, also loved to join in a little fun.

Bench 5 was Mr E Settle, a great tennis player as well as a super joiner. We made windows and window sashes – if I went over his lines on the hand mortice machine, I was in serious trouble. He believed in strict discipline and it had to be obeyed; I liked him.

Tom Durham and apprentice Boyn Watson were on Bench

7.

Apprentice games

At that time each tradesman had a lad with him. Their full union rate of pay was £2-18-0 to £3 per week. My pay started at 7/6 per week. At 21, my last year, it was £1-10-0.

We all had to join in the fortnightly Union Club Meeting at the Crown Inn rooms in Ouse Street. It became one of the lads' greatest nights out, the memories unforgettable.

The Crown Inn, Ouse Street, Goole is on the left; it is the first taller building with a man outside

Once Frank, our leader, was asked to bring our Harry Temple a new G string from Leeds to repair his violin. This he did and on the club night we met him to carry his case.

After all the A.S.W. [Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers] business finished [it was announced], "Now brothers, Mr Harry Temple will give us his rendition of Danny Boy on the violin." Well, after getting the key note on the old piano, Harry, with his walrus moustache, struck up with "Londonderry Air".

Frank was hid in the corner of the room making a noise like a cat 'meowing' and we were all in stitches holding in laughter, when Harry stopped and said, "Can't someone put that bloody cat outside?"

Frank [plagued the life out of] of some of the old joiners. His mate Sam didn't know what to expect next. One day he was furious; all his wood planes were neatly at the bench end but Frank had glued [one of] Sam's planes to the bench and cut the top of a 6" nail off with a hacksaw and placed it on top of Sam's plane to look as if it was nailed to the bench.

General repairers

On the two spare shop benches were the two outside repair joiners. I had a year with Mike Ellis and did repairs to wood spouts, gates, window sash re-cording, any property repairs, renewing passage wood floors, fixing joists and mat wells etc.

Fungus attacked Goole property quite a lot. Mr Featherstone once showed me a bay window in Clifton Gardens eaten away with fungus, just the paintwork left.

My next repair mate was Harold Rowley, never a dull moment. We had to work in conjunction with bricklayer repairers. Mr Bob Wright was doing property repairs on a farm on Goole Fields. One day while repairing and renewing the front door entrance, we dropped into a deep unused cellar. There we found some bottles of wine and began to help ourselves. This turned out to be very potent, with the result that while the farmers were in Goole shopping we had drinks all round. This made its mark on our legs as we walked to The Barracks for our transport home at night.

New houses at Hook

Next I was sent with Mr Jack Causon to cut the roofs out for eight new houses built at Hook for Mr Hall, who'd just returned with his money from the Canada gold mines. He bought the piece of land just through the railway bridge. He told me he had shares in a gold mine in Canada and when a good price for selling appeared, he sold out as his wife wanted to be living near her sister, Mrs Charles Wilson.

This joiner, Mr Jack Causon, was the best roof joiner in the county and that's a rash statement. But he could read all the rafter cuts of any roof one put in front of him by reading two ordinary 2 foot wood rules. He could also do the same with flights of stairs. We cut the roof out with a minimum of waste timber. Mr Featherstone would have his building hips mitred down in the corner of the wall and dressed to paint white in the bedrooms where other builders would fix a dog timber across the pan. The spans down the hip were all cut from 16ft 4" x 2". What was cut off the long point was used in at the low point, each making two complete spans and no waste.

On getting the ridge fixed, we hung up the Union Jack flag on the first house.

"What’s the flag for?" inquired Mr Hall.

"It's a gesture, Sir, to the owner; it calls for drinks all round."

In the afternoon Mr Hall was there with a case of beer and cigarettes for all. Those eight houses were really well built - NO shoddy work with Platt and Featherstone.

Mr Herbert Featherstone

Mr Featherstone visited everyday, not in a car - on his bike. He was never aggressive and if something had gone wrong, he never talked a great deal, but his job was to see everything was correct and of top standard. I've watched him; his eye would sight two casings with the window or glance at the mitres on skirting architrave. The teamwork between master and worker was never as high as Platt & Featherstone in those days.

In the days or weeks before Christmas, when frost was about, we did not build. This called for men to be laid off for a while. Mr Featherstone would come into our joiners' shop very down and glum, walk all around the shop collecting shavings in his hand and tear them apart, then straight out and down the yard. Joiners knew it was to happen before Xmas. If there was one thing that distressed Herbert Featherstone more was to sack or stand a man off, I never knew it. This great man has now passed on; I saw him a year before he died, still working, still his white apron on. I said I'd just called to see him. This man was and will be forever in my eyes a true great master craftsman and boss.

On finishing the roofs of eight houses we fixed the downstairs floor joists and a little second fixing which amounted to fixing doors, architraves, skirting, cupboards etc. I had been using Jack's panel saw quite a lot and he had noticed. He could bend this saw, putting the tip through the handle, and return without a bend. He had three or four handsaws, all in tip top condition.

Our firm was very busy at that time; they got a large contract for the new Driffield Hospital and Jack had to go take over the site foreman's job. I had to pack my tools and go second fix Mr Milner's bungalow. I was up Hook Road 200 yards away when Jack came and presented me with this panel saw. If I'd received £50 my eyes could not have lit more. I treasure that saw to this day. When we lived at Goole, 40 Queensway, I got out of bed one night, dressed and walked two streets away, well after midnight to recover this saw that I knew I'd left out. I’ve used it on every job for 40 years.

Completing my apprenticeship

The bungalow was finished in the last year of my apprenticeship. I started at 15 years old, and during the 6 years Platt and Featherstone had built some major big buildings, in and out of Goole.

These included Goole's new Post Office, then Goole's clock tower and lavatories, the Crescent Working Men's Club, the bandstand in Riverside Park, all the council houses in Mond Avenue and Cambridge Avenue and the large new hospital at Driffield.

The great day, 14th July, came. I was 21 and entitled to full tradesman's money - £2-18-0 per week. I worked my last year at apprentice rate £1-10-0 per week. Mr Featherstone sent me to the office to see Mr Bob Sedlon, the only office clerk and pay clerk employed. I was paid full rate. Bob started as a lad and finished same time as the firm broke up.

The following week I was paid full rate but Bob explained that the first slack time I should get the sack in preference of more experienced tradesmen.

Working at Goole Shipbuilding

This happened after 6 months, but I was lucky. Two large grain ships, SS Eder and SS Fylgia, came to Goole Shipbuilding Yard to be converted into passenger ships for the Great American Lakes. The ships had to be [?] for rats, blue in colour; they could run on a ceiling like a fly upside down. After being stripped and cleaned to the skin, the boats were rebuilt with lovely wide companionway steps in oak to the centre of the ships. Of course, everything in woodwork is different to house building: instead of being plumb, on ships everything is on the shore or bevel.

Mr Fred Spence was my foreman, very clever chap. All the shipyard men were all A.S.W. members. I stayed with them until the ships were completed and renamed ? and SS Bolivar. Work at the shipyard got slack after these were completed. Ted, Tom and I left and started 6am to 6pm at Ferry Bridge, the new power station, building shutters, travelling in Ted's Ford 8 little car, sharing his petrol expenses.

Changing jobs

After six months on that job we moved to Burton Stather on the River Trent, building a large jetty. Here I had an accident while working on the open jetty at high water. A skip of cement on the jib of the large crane hit my head and knocked me into the river. My jacket had a large hammer in one pocket and 6" nails in the other. My head was in the water. Ted saw my plight and, with a boat hook in my britches backside, he pulled me out. This was at 9am in the morning in winter. I wore an old mac until 5 o'clock finishing time and had all my wet clothes in a nail bag; I was very cold and miserable. I had the next day off work.

I could not settle on that job after that – one of our joiners had been killed by accidentally dropping down the New Ocean Lock Pit at Goole.

I applied and got a job at home, all rough work but good money and more time with my family at Skelton.

After this work I started for Bovis, a London firm, to build a new Marks & Spencers shop in Boothferry Road, Goole. I stayed with that firm until the day the new shop opened under a cockney swine of a foreman, who got the sack for fiddling cash before the job was half finished. I was saving money to get married, then I got the sack at 10 o'clock in the morning and we married at 1 o'clock the same Saturday.

Happy days at the shipyard

After a fortnight out of work, I got work in Mr Cragg's shipyard at Goole, bench work in the joiners' shop with Fred Upton for a bench mate. Like home, I was very happy amongst those lads. Tip top foreman, Fred Spence, also a genius of a machinist called Jim Newell.

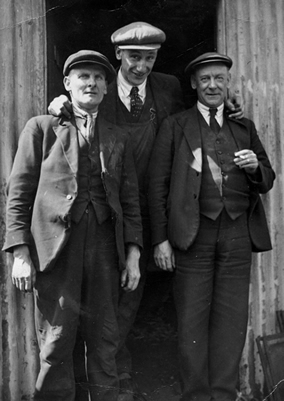

Mr Harry Durham (centre) and workmates, thought to be pictured at Goole Shipyard

We built the wheel house all in solid teak, varnished, and [it] looked very rich. All the ship's furniture was made in hard woods and French polished by another genius of polish, old Jack Hutton and his son Les. To me, these men were of outstanding quality - if the bed fronts or wardrobes, washstands etc were not cleaned and scraped to standard for French polish, one had to return to the bench and do so.

Our foreman gave Jack that instruction, which was the reason everything looked so rich in colour and perfection.

My work was a great pleasure in the shipyard; the men are still my friends.

Getting married

At home at Skelton I was very happy. Vida of No. 3 and I liked each other’s company. She left school when she was around 16 years of age to start work as a riveter at Howden Aerodrome helping to build the R100, cycling 12 miles per day, 6 miles to and from for around 12/6 per week. She beat my 7/6 apprentice money. When the airship was launched [in 1929], Vi was very quickly offered work as a housemaid at Bridlington. This put paid to our friendship. Her father brought her home around once a month on his Norton motorcycle and sidecar outfit and on these occasions we made the happiest weekends together, visiting the pictures at Goole.

My happiest day was when she applied for a job as a housemaid at Dr Crawford's at Goole and was accepted. We married from there.

We rented a house in the middle of the row of five cottages, my parents at one end house and Vi's parents at the other. This cost us 4/6 per week rent, paid at Goole station.

The Friday before the Saturday we were married, I got the sack. I'd been working on the new Marks & Spencer shop in Goole; it was opened the same Saturday afternoon. [Harry married Vida Jefferson on 31st March 1934.]

After being out of work a fortnight, during which we made a little oak bedroom suite in the back scullery, Vi helping and sweeping up the shavings, I had £20 in the bank' Vi had £18. We decided to spend mine and reserve Vi's. I went to a sale at Howden and bought a seven piece sitting room suite which consisted of a drop end settee, two arm chairs and four dining room chairs - £9 total. Vi and I visited Hull and bought a bedroom suite, £12. Vi got a round dining table and she had collected pots, towels, sheets and blankets. After that first fortnight, we were broke.

Saved by the bell, I found work building Capper Pass at Ferriby, near Hull. I was sent with twenty other joiners: "With your tools, be on site 8 o'clock Monday morning."

We were all assembled in a large hut and the foreman said, "There's the timber; make yourself a saw stool and a nail box. I’ll be back."

On return he just said, "You, you, you,” and picked around ten. My mate Eric Lowther and I from Goole were included. We worked on that site until it was completed.

I asked Joe Hackett, our foreman, later why the saw stool and nail box. His answer was, "Didn't you witness the specimens that was made!"

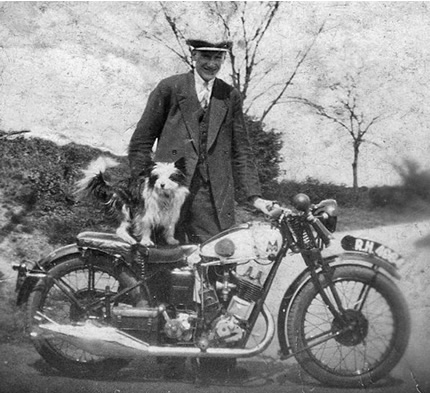

Mr Harry Durham, pictured with Mick on the motorbike